1998 Tour de France

Route of the 1998 Tour de France | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Race details | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Dates | 11 July – 2 August 1998 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Stages | 21 + Prologue | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Distance | 3,875 km (2,408 mi) | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Winning time | 92h 49' 46" | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Results | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

The 1998 Tour de France was the 85th edition of the Tour de France, one of cycling's Grand Tours. The 3,875 km (2,408 mi) race was composed of 21 stages and a prologue. It started on 11 July in Ireland before taking an anti-clockwise route through France to finish in Paris on 2 August. Marco Pantani of Mercatone Uno–Bianchi won the overall general classification, with Team Telekom's Jan Ullrich, the defending champion, and Cofidis rider Bobby Julich finishing on the podium in second and third respectively.

The general classification leader's yellow jersey was first awarded to Chris Boardman of the GAN team, who won the prologue in Dublin. Following a crash by Boardman on stage 2 that caused his withdrawal, Ullrich's sprinter teammate Erik Zabel took the race lead. He lost it the next stage to Casino–Ag2r's Bo Hamburger, who took it after being in a breakaway. The day after, the yellow jersey switched to another rider from the same breakaway, Boardman's teammate Stuart O'Grady, who took vital seconds from time bonuses gained in intermediate sprints. He held it for a further three stages, until pre-race favourite Ullrich won stage 7's individual time trial, moving him into the overall lead. The next day, Laurent Desbiens of Cofidis finished in a breakaway with a large enough margin to put him in the yellow jersey. Ullrich regained the race lead two stages later as the Tour went into the Pyrenees. Following his poor showing in the opening week, Pantani placed second and first, respectively, on the two Pyreneean stages. He then won stage 15, the first in the Alps, to replace Ullrich in the yellow jersey, and kept it until the race's conclusion.

Zabel won his third consecutive Tour points classification and Julich's teammate Christophe Rinero, fourth overall, was the winner of the mountains classification. Ullrich was the best young rider and the most combative was Casino–Ag2r's Jacky Durand. The team classification was won by Cofidis. Tom Steels of Mapei–Bricobi won the most stages, with four.

The race was marred throughout by a doping scandal, known as the Festina affair. Before the Tour began, Willy Voet, an assistant of the Festina team, was arrested at the Franco-Belgian border when doping products were found in his car. The affair broadened and the team was expelled after top personnel admitted to widespread doping. Police raids on numerous teams during the course of the race led to two riders' strikes and the withdrawal of several teams and riders. Due to the controversy, the race became known by the nickname "Tour de Farce". In July 2013, retrospective tests for recombinant EPO made in 2004 were made public, revealing that 44 out of 60 samples returned positive tests.

Teams

[edit]

The organisers of the Tour, Amaury Sport Organisation (ASO), cut the number of teams from 22 to 21 for the 1998 Tour, to reduce the number of crashes in the opening week of the race seen in recent editions, caused by the large number of riders.[1] The first round of squads that were invited were the first sixteen teams in the ranking system of the Union Cycliste Internationale (UCI), cycling's governing body, on 1 January 1998, provided that they were still in the top twenty after transfers were factored into the calculation.[2] All these sixteen teams fulfilled this requirement.[3] On 19 June, the ASO gave wildcard invitations to Asics–CGA, Cofidis, Riso Scotti–MG Maglificio and Vitalicio Seguros, with BigMat–Auber 93 receiving a special invitation.[4] The presentation of the teams – where the members of each team's roster are introduced in front of the media and local dignitaries – took place outside the Front Gate of Trinity College Dublin in Ireland on the evening before the prologue stage, which began at the college.[5]

Each squad was allowed a maximum of nine riders, resulting in a start list total of 189 riders.[6] Of these, 51 were riding the Tour de France for the first time.[7] The riders came from 22 countries, with the majority of them coming from France, Italy and Spain.[6] Jörg Jaksche (Team Polti) was the youngest rider at 21 years and 353 days on the day of the prologue, and the oldest was Massimo Podenzana (Mercatone Uno–Bianchi) at 36 years and 347 days.[8] The Team Polti cyclists had the youngest average age while the riders on Mercatone Uno–Bianchi had the oldest.[9]

The teams entering the race were:[6]

Qualified teams

Invited teams

Pre-race favourites

[edit]

Jan Ullrich (Team Telekom) was the defending champion. He had won the 1997 edition's overall general classification by over nine minutes.[10] His Telekom team was considered as "clearly the squad to beat",[11] having won the previous two editions with Bjarne Riis and Ullrich respectively.[12] The 1997 Tour had seen a contest for leadership between Telekom's two captains, but for 1998 this had been resolved in Ullrich's favour.[13] During the winter break, Ullrich's training was impaired by the consequences of the fame and fortune that came with his Tour win,[14][15] and his weight had increased from 73 kg (161 lb) to 87 kg (192 lb).[13] In March 1998, El País headlined an article with "Ullrich is fat", which highlighted that he was still 8 kg (18 lb) over the weight he had during the previous Tour.[16] His preparation suffered further when he was forced to retire from Tirreno–Adriatico with a cold.[16] However, Ullrich performed well in both the Tour de Suisse and the Route du Sud directly before the start of the Tour, erasing doubts over his form.[17] He was therefore thought to be the clear favourite going into the 1998 Tour,[14][15][18][19] with El País going so far as to write that "we can no longer speak of an open Tour, of a deck of suitors. There is talk of Ullrich, and then of the others."[20] The route of the race was considered to be an advantage to Ullrich as well, with many time-trial kilometres and comparatively few mountain passes.[17] The veteran Riis, who had raced the 1997 Tour with a cold, was seen as a capable backup option for the team.[15]

The strongest challenge was expected to come from Festina–Lotus,[17] which led the UCI team ranking prior to the start of the Tour.[21] Their leading rider, Richard Virenque, had finished second to Ullrich the year before. The two long individual time trials were expected not to be in Virenque's favour, since he did not excel in the discipline.[17] He was however a very good climber, having won the mountains classification in the four previous Tours.[22] The team was further strengthened by the arrival of Alex Zülle in the 1998 season, winner of the two previous editions of the three-week Grand Tour of Spain, the Vuelta a España, who was considered to be a competitor for overall victory in his own right.[23][24] He was a leading pre-race favourite at Italy's Grand Tour, the Giro d'Italia,[25][26] one month earlier, winning two of the three time trial stages and leading the race before he faltered badly in the final mountain stages to end the race in 14th overall.[25][27] Another possible contender from Festina was Laurent Dufaux, who had finished fourth overall in 1996 and ninth in 1997.[17]

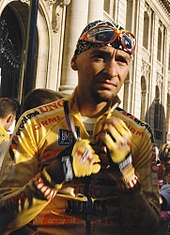

Marco Pantani (Mercatone Uno–Bianchi) was considered the "dominant climber in the sport" at the time.[17] In June, he had taken an "exceptionally impressive"[28] overall victory at the Giro.[26] Of his three appearances in the Tour up to that point, he had finished third in two of them, including in 1997.[29] When the Tour's route was announced in October 1997, Pantani expressed dissatisfaction with the number of time trials and the fact that the race featured only two mountain-top finishes. Since the route was not to his liking, he originally had shown no interest in riding the race. Following his victory at the Giro, Pantani raced only once, a criterium race in Bologna. His decision to ride the Tour was not made until Luciano Pezzi, his closest confidant and an important figure at Mercatone Uno, died suddenly in late June. Pantani decided to go to the Tour in honour of Pezzi, but had done very little training beforehand.[30] A further disadvantage to Pantani was his lack of a strong domestique, unlike Ullrich and Virenque.[29]

A returning pre-race favourite from the 1997 Tour was time trialist Abraham Olano; in that race, he won the final time trial stage and placed fourth overall.[15][31] He led the experienced Banesto team, who took Miguel Induráin to his five straight Tour wins between 1991 and 1995,[31][32] and had been seen as his successor.[15][31] His weakness was thought to be his lack of strength on steep climbs.[31] In his final race leading up to the Tour, the Volta a Catalunya, he performed poorly in the high mountains,[15] and as a result was only seen as a podium contender.[15][31] Banesto also fielded José María Jiménez, who as a strong mountain rider was considered a "major threat".[28]

The final rider noted as a leading contender, named "the outsider", was the ONCE team leader Laurent Jalabert, a complete all-rounder who excelled in all road cycling disciplines.[33] Although he was the reigning time trial world champion and the clear first in the UCI individual ranking before the Tour,[15][21] he had only aimed to match his overall placing of fourth in 1995.[15] The riders also named as outside favourites for overall victory were Michael Boogerd (Rabobank),[17] Cofidis riders Francesco Casagrande and Bobby Julich, Evgeni Berzin (Française des Jeux), Fernando Escartín (Kelme–Costa Blanca), and Chris Boardman (GAN).[34]

Route and stages

[edit]

The route of the 1998 Tour de France was officially announced during a presentation at the Palais des congrès in Paris on 23 October 1997.[35][36] First negotiations about a potential start of the race in Ireland took place in October 1996, with the Irish government securing funding of IR£2 million to host the event.[37] The opening stages (known as the Grand Départ) in Ireland were confirmed in early April 1997.[38] Irish officials expected the race to bring in IR£30 million to the local economy.[39] It was the first and so far only time that the Tour has visited Ireland.[1] The race paid tribute to two famous former Irish professional cyclists: on the day before the prologue, a commemoration service was held in Kilmacanogue for Shay Elliott, the first Irish rider to ride the Tour and win a stage,[40] and during stage 2 of the race, the route went through Carrick-on-Suir, the hometown of Sean Kelly, four-time winner of the Tour's points classification.[41][42] Stage 2 also commemorated the 200th anniversary of French troops landing at Killala Bay during the Irish Rebellion of 1798.[43]

The 1998 Tour was pushed back one week from its original start date, so as not to overlap too much with the 1998 FIFA World Cup, also held in France, which ended on 12 July, one day after the prologue.[44] The 3,875 km (2,408 mi)-race lasted 23 days, including the rest day, and ended on 2 August.[45][46] The longest mass-start stage was the fourth at 252 km (157 mi), and stage 20 was the shortest at 125 km (78 mi).[46] The race contained three individual time trials, one of which was the prologue, totalling 115.6 km (71.8 mi).[14] Of the remaining stages, twelve were officially classified as flat, two as mountain and five as high mountain.[2] There were only two summit finishes,[19] which were both at ski resorts, one at Plateau de Beille on stage 11 and another on stage 15 at Les Deux Alpes.[1] The highest point of elevation in the race was 2,642 m (8,668 ft) at the summit of the Col du Galibier mountain pass on stage 15.[47][48] It was among five hors catégorie (beyond category) rated climbs in the race.[49][50][51][52] Cycling journalist Samuel Abt considered the route easier than the 1997 edition.[36] Tour director Jean-Marie Leblanc countered criticism by Virenque and Pantani that the race was not mountainous enough, saying: "The course is tough enough with 23 mountains. That is eight more than last year."[1]

The Tour started with a prologue time trial around the streets of Dublin. Stage 1 was a loop that returned to the city, with the following stage travelling down the Irish eastern coast to Cork.[35] The riders then travelled to France by plane,[53] with the team vehicles and equipment following by sea.[54] Just as the year before, the Tour took a counter-clockwise route through France.[55] The course in France started in Roscoff in the north-western region of Brittany, with three stages taking the race to the centre of the country at Châteauroux. Stage 6 moved the Tour into the Massif Central highlands, which hosted the next stage. Two transitional stages to Pau then placed the race in the foothills of the Pyrenees, where two stages took place. Following the rest day, a three-stage journey crossed the south to three further stages in the Alps. The next stage took the Tour through the Jura Mountains to Switzerland, with the following stage crossing back over the border to Burgundy, where the penultimate stage took place. After a long transfer to the outskirts of Paris, the race ended with the Champs-Élysées stage.[56]

| Stage | Date | Course | Distance | Type | Winner | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| P | 11 July | Dublin (Ireland) | 5.6 km (3 mi) | Individual time trial | ||

| 1 | 12 July | Dublin (Ireland) | 180.5 km (112 mi) | Flat stage | ||

| 2 | 13 July | Enniscorthy (Ireland) to Cork (Ireland) | 205.5 km (128 mi) | Flat stage | ||

| 3 | 14 July | Roscoff to Lorient | 169 km (105 mi) | Flat stage | ||

| 4 | 15 July | Plouay to Cholet | 252 km (157 mi) | Flat stage | ||

| 5 | 16 July | Cholet to Châteauroux | 228.5 km (142 mi) | Flat stage | ||

| 6 | 17 July | La Châtre to Brive-la-Gaillarde | 204.5 km (127 mi) | Flat stage | ||

| 7 | 18 July | Meyrignac-l'Église to Corrèze | 58 km (36 mi) | Individual time trial | ||

| 8 | 19 July | Brive-la-Gaillarde to Montauban | 190.5 km (118 mi) | Flat stage | ||

| 9 | 20 July | Montauban to Pau | 210 km (130 mi) | Flat stage | ||

| 10 | 21 July | Pau to Luchon | 196.5 km (122 mi) | High mountain stage | ||

| 11 | 22 July | Luchon to Plateau de Beille | 170 km (106 mi) | High mountain stage | ||

| 23 July | Ariège | Rest day | ||||

| 12 | 24 July | Tarascon-sur-Ariège to Cap d'Agde | 190 km (118 mi)[a] | Flat stage | ||

| 13 | 25 July | Frontignan la Peyrade to Carpentras | 196 km (122 mi) | Flat stage | ||

| 14 | 26 July | Valréas to Grenoble | 186.5 km (116 mi) | Mountain stage | ||

| 15 | 27 July | Grenoble to Les Deux Alpes | 189 km (117 mi) | High mountain stage | ||

| 16 | 28 July | Vizille to Albertville | 204 km (127 mi) | High mountain stage | ||

| 17 | 29 July | Albertville to Aix-les-Bains | 149 km (93 mi) | High mountain stage | —[b] | |

| 18 | 30 July | Aix-les-Bains to Neuchâtel (Switzerland) | 218.5 km (136 mi) | Mountain stage | ||

| 19 | 31 July | La Chaux-de-Fonds (Switzerland) to Autun | 242 km (150 mi) | Flat stage | ||

| 20 | 1 August | Montceau-les-Mines to Le Creusot | 52 km (32 mi) | Individual time trial | ||

| 21 | 2 August | Melun to Paris (Champs-Élysées) | 147.5 km (92 mi) | Flat stage | ||

| Total | 3,875 km (2,408 mi)[45] | |||||

Race overview

[edit]Pre-Tour revelations

[edit]On 4 March 1998, a truck belonging to the Dutch TVM–Farm Frites team was seized by customs officers in Reims, France, revealing 104 vials of recombinant erythropoietin (EPO), a drug with performance-enhancing effects. The two mechanics in the truck were released and the vials were taken by the police, who said they had more "important matters" to be concerned with.[60][61] During the Critérium du Dauphiné Libéré, a race held two weeks before the start of the Tour, Christophe Moreau of Festina tested positive for the anabolic steroid mesterolone.[62] The UCI accepted Festina's explanation that the positive test was a result of the influence of a team masseur, and Moreau was allowed to start the Tour de France.[63]

Three days before the start of the Tour, on 8 July, Willy Voet, a soigneur (team assistant) with the Festina squad, was stopped by customs officers driving along a back road on the Franco–Belgian border.[64] A routine check revealed that he carried a large quantity of performance-enhancing drugs with him.[c] He was thereafter placed under arrest, initially claiming they were "for personal use".[64] The following day, police carried out a search of Festina's headquarters in Meyzieu, close to Lyon.[66] On the day before the prologue, a judicial inquiry was opened by the public prosecutor's office and Voet was held for investigation,[66] with the story also breaking to the media.[65] The Tour's organisation as well as Festina were quick to dismiss the news as having nothing to do with the race.[67][68]

Early stages in Ireland

[edit]

Chris Boardman covered the 5.6 km (3.5 mi) route of the prologue time trial fastest with a time of 6:12.36 minutes,[69] gaining his third Tour prologue victory.[70] Olano finished second, four seconds slower. Third to sixth place went to Jalabert, Julich, Moreau, and Ullrich, all five seconds behind Boardman.[69] Marco Pantani meanwhile had not bothered to preview the course and finished 181st out of the 189 starters, 48 seconds slower than the winning time.[71] Boardman was awarded the yellow and green jerseys as the leader of both the general and points classification respectively.[72]

Tom Steels outsprinted Erik Zabel in stage 1's bunch sprint finish.[73] Steels came to the Tour with the full support of his Mapei–Bricobi squad for the sprints, unlike Zabel's Team Telekom who were focused on Ullrich's pursuit for overall victory.[53] Mario Cipollini (Saeco–Cannondale), a favourite for the stage win, was held up 8 km (5.0 mi) from the end when he was involved in a crash with his teammate, Frédéric Moncassin.[74][75] Steels took the lead of the points classification from Boardman, who retained the overall lead.[72] Steels's teammate Stefano Zanini was the first of a seven-rider breakaway group to reach the summit of the Wicklow Gap mountain pass, claiming the Tour's first available mountains classification points and the first polka-dot jersey.[72][76]

Unlike other general classification favourites, who always rode at the front of the peloton (main group), Pantani spent the first days of the Tour at the back, surrounded by his teammates.[71][d] This almost cost him, when during stage 2, which was raced largely on the wide N25 road,[78] crosswinds split the field into several echelons. Pantani was caught out and only came back when yellow jersey-wearer Boardman crashed heavily. In the aftermath, the peloton slowed down, allowing Pantani to catch back up.[79] Boardman meanwhile hit his head badly on a stone wall beside the road. He was taken to hospital and had to abandon the Tour.[80] Mapei–Bricobi rider Ján Svorada was involved in a crash with 15 km (9.3 mi) to go, but was able to recover and win the bunch sprint finish.[81] Zabel, who before the stage stood in eighth position overall,[82] had collected enough time bonuses in the intermediate sprints to take the yellow jersey.[83]

Move to France and evolving doping scandal

[edit]

Team Telekom's Jens Heppner won stage 3 from a two-rider sprint with Xavier Jan of Française des Jeux, after the pair had escaped late from a nine-rider breakaway. Bo Hamburger of Casino–Ag2r, who won two of the three intermediate sprints whilst in the escape group, took the overall lead.[84] Svorada took the lead of the points classification, while Festina's Pascal Hervé led the mountains classification.[72] The second and third-placed riders in the now much-changed general classification also came from the breakaway, with George Hincapie (U.S. Postal Service) two seconds down on Hamburger, and Stuart O'Grady (GAN) a further second behind.[85] Hincapie and O'Grady went head to head for the time bonuses in stage 4's three intermediate sprints in pursuit of the race lead. O'Grady won two of them to end the day with an eleven-second overall advantage over both Hincapie and Hamburger. The stage was won by Jeroen Blijlevens (TVM) from an uphill bunch sprint at Cholet in the Loire Valley.[86][87] Cipollini suffered his third crash of the Tour at the end of stage 4,[88] accumulating eight separate injuries,[89] but was able to avoid the multiple crashes in the next stage to win the bunch sprint finish.[90] Svorada was disqualified for causing a crash at the end of the stage, losing the points he had earned from his tenth-place finish. Svorada's green jersey went to Zabel, who finished second in the stage.[91] Cipollini won the following stage, from a bunch sprint into Brive-la-Gaillarde.[92]

As the ferry reached French soil overnight into 14 July, the day of stage 3, all team vehicles were meticulously searched at customs.[54] During the day, Voet admitted to police that he had been following team orders, with Festina's team doctor Eric Rijkaert publicly denying he administered any banned substances. The next day, the team manager Bruno Roussel and Rijkaert were taken into police custody.[66] Before the start of stage 5,[93] Jean-Marie Leblanc announced at a press conference that the professional licences held by Roussel and Rijkaert had been provisionally suspended by the UCI. At the same time, Festina riders Richard Virenque, Laurent Brochard and Laurent Dufaux stated their intention to carry on racing.[66] During stage 6, Roussel and Rijkaert confessed to systematic doping in the Festina squad. This led to the Tour organisation to expel the team ahead of the following stage.[94]

Before the start of stage 7 Virenque, on behalf of Festina, held a private meeting with Leblanc to plead for the team to be allowed to continue, but to no avail.[95]

Stage 7, the hilly and technical first long individual time trial, was won by Ullrich, 1:10 minutes ahead of U.S. Postal Service's Tyler Hamilton, with Julich in third a further eight seconds behind. O'Grady was fifteenth with a deficit of 3:17 minutes, and lost the yellow jersey to Ullrich, who was now 1:18 minutes in front of Hamburger and Julich on the same time in second and third respectively. Pantani finished thirty-third, 4:21 minutes slower than Ullrich, he said later that he had held himself back in anticipation of the upcoming Pyrenees.[96] Zanini regained the polka dot jersey.[72] Stage 8 was held in very high temperatures. A group of six riders reached the finish 7:45 minutes ahead of the peloton. The sprint was won by Jacky Durand of Casino–Ag2r, who had been in an escape group on every road stage so far. Four riders from the group gained enough time to move to the top of the general classification, with Cofidis's Laurent Desbiens taking the yellow jersey.[97] Temperatures increased to a high of 44 °C (111 °F) during the following stage, which was won by Rabobank rider Léon van Bon in a final sprint, contested between a four-man breakaway. The closing field followed 12 seconds later. Second-place finisher Jens Voigt (GAN) collected enough mountains classification points from within the breakaway to take the polka-dot jersey.[98] Two-time stage winner Cipollini dropped out during this stage.[99][e]

Pyrenees

[edit]

Stage 10 saw the race move into the high mountains, starting with the Pyrenees. On the way to Luchon, four mountain passes had to be crossed: the Col d'Aubisque, the Col du Tourmalet, the Col d'Aspin and finally the Col de Peyresourde, followed by 15.5 km (9.6 mi) of downhill to the finish line.[102] A total of 30 riders fell on the wet and foggy descent of the Aubisque, including overall contenders Olano, Jalabert and Francesco Casagrande,[103] with the latter being one of six that retired from the race.[102] A three-rider breakaway of Cédric Vasseur (GAN) and Casino–Ag2r teammates Rodolfo Massi and Alberto Elli formed by the foot of the Tourmalet. The pace set by Team Telekom halfway up this climb split the peloton, with yellow jersey wearer Desbiens dropped. Massi moved clear from his fellow riders in the breakaway group on the steep section midway on the 13 km (8.1 mi)-long last climb, and also at the same point after, a move by Ullrich formed a small group of elite riders which included pre-race favourites Pantani, Julich, Riis, Boogerd, Escartín and Jiménez. Close to the top, Pantani launched a successful attack and summitted with an advantage of 42 seconds, but was unable to catch the soloing Massi on the descent,[104] who took the stage victory as well as the lead of the mountains classification.[102] Pantani finished second, 33 seconds behind. Ullrich followed with the other favourites, a further 23 seconds back, to regain the yellow jersey, while Julich moved up to second overall.[105]

The following stage 11 featured the first mountain-top finish of the 1998 Tour. The peloton agreed not to begin racing until after the first 45 km (28 mi), when they stopped to pay their respects at the memorial to Fabio Casartelli on the Col de Portet d'Aspet, who crashed and died there during the 1995 Tour.[106][107] As the field reached the bottom of the 16 km (9.9 mi) climb to the finish at Plateau de Beille, Ullrich had a tyre puncture. Pantani was unaware of this and was about to attack, before being stopped by his teammate Roberto Conti, as it breaches the unwritten rules of the peloton to attack a rider when they have mechanical issues. Having waited for Ullrich to regain contact, Pantani waited until 4 km (2.5 mi) from the finish to attack, and after passing the sole breakaway rider, Roland Meier (Cofidis), he took the stage win.[108][109] Following Meier and a group of five led by Julich, Ullrich crossed the finish line in eighth place, 1:40 minutes down on Pantani. After the two stages in the Pyrenees, Ullrich led the general classification, 1:11 minutes ahead of Julich, with both Jalabert and Pantani 3:01 minutes down in third and fourth.[110] Olano, a notable pre-race favourite, withdrew from the Tour halfway through the stage.[111]

Transition stages and rider unrest

[edit]

After the rest day, stage 12 followed a flat course between Tarascon-sur-Ariège and Cap d'Agde. The riders were unhappy with the looming expulsion of the TVM team, against which the police had renewed their investigation which was started in March. Likewise, journalists going through waste containers at team hotels, searching for evidence of performance-enhancing drugs, drew anger from the peloton. Some riders also spoke out against the announcement by the UCI to move forward the introduction of new health tests.[112] As the riders lined up with their bikes at the start of the stage, Jalabert broadcast a statement on their behalf on the race's official station, Radio Tour, saying "We are fed up with being treated like cattle. So we are going to behave like cattle."[113]

Following this, the majority of the riders sat down on the road and refused to continue, while others willing to start stood around, unsure what to do.[113] The instigators of the strike were Jalabert, Blijlevens, Max Sciandri (Française des Jeux), and Prudencio Induráin (Vitalicio Seguros) as well as ONCE's team manager Manolo Saiz.[114] Leblanc negotiated with the team managers and they voted 14–6 in agreement to begin the stage. The peloton and vehicles slowly set off, but a Jalabert-led group of about 40 refused. They eventually relented and caught up to the rest 16 km (9.9 mi) ahead, and the race started, exactly two hours after the scheduled time. It was at this point that the stage was officially started.[115] After about 40 km (25 mi), Jalabert then went on the attack over a short climb with his brother Nicolas (Cofidis) and Bart Voskamp (TVM),[116] with the group building up a lead of about five minutes.[115] Team Telekom gave chase at a high pace, temporarily putting Pantani into difficulty as crosswinds created echelons in the peloton.[117][118] The trio of escapees were eventually brought back. Steels took his second stage win of the Tour in a bunch sprint finish, but withheld any celebrations following the events of the stage.[119][116] The stage, shortened by 16 km (9.9 mi) to account for the delay caused by the strike, was run at an average speed of 48.764 km/h (30.301 mph), the third-fastest stage in Tour history.[120]

Stage 13 saw a breakaway by six riders, among them Daniele Nardello and Andrea Tafi, both of Team Mapei–Bricobi. They worked together at the finish to ensure Nardello took Mapei's fourth stage win. At the only classified climb of the day, Luc Leblanc (Team Polti) put in an attack, but was brought back by Riis.[121] The following day's stage brought the Tour to Grenoble at the foot of the Alps. The stage was won by O'Grady, again from a breakaway.[122] In the press conference after, Ullrich was asked whether his team would be capable of supporting him in the Alps and, after initially appearing upbeat, he ended his response with: "Even if I don't have the yellow jersey in Paris, I want to give my compliments to the team".[123] Pantani, who still stood at fourth overall, was quoted saying: "My main goal now is to win in Les Deux-Alpes."[122]

Alps and second strike

[edit]

Stage 15 was the first of three Alpine stages. After a warm start in Grenoble, the weather soon deteriorated, with cold temperatures, rain and fog impeding the riders. The route contained four classified climbs, including the hors categorie Col de la Croix de Fer and Col du Galibier, and ending with a summit finish at Les Deux Alpes.[124] On the Croix de Fer, Massi bridged over to a breakaway group and scored maximum points for the mountains classification, a feat he repeated on the second climb of the day, the Col du Télégraphe. By this point, the lead group contained only Massi, Christophe Rinero (Cofidis) and Marcos-Antonio Serrano (Kelme–Costa Blanca). Behind them in the group of the main favourites, the high climbing tempo put Jalabert into difficulty, which ultimately saw him drop far down the general classification by the end of the stage.[125] After the short descent of the Télégraphe, the race reached the Galibier, where Riis cracked following his work reeling back attackers, leaving Ullrich without a teammate.[126] With 6 km (3.7 mi) remaining to the summit of the Galibier, Pantani made the decisive move of the race, attacking from the group of favourites.[127] By the summit of the climb, Pantani had passed all the breakaway riders and was out in front alone, leading by ten seconds. Ullrich reached the top 2:41 minutes behind Pantani. Crucially, unlike Pantani, he did not wear a raincoat during the descent. He subsequently suffered from the cold temperatures and hypoglycemia for the rest of the stage.[128] The breakaway caught up to Pantani on the descent of the Galibier, forming a group of strong climbers. Before the final climb to Les Deux Alpes, Ullrich had a tyre puncture and was distanced by the group of chasers. On the climb, Pantani soon moved clear of his group and took the stage victory, almost two minutes ahead of Massi in second place. Ullrich finished with teammates Udo Bölts and Riis 8:57 minutes after Pantani, who took over the yellow jersey. He led Julich by 3:53 minutes, with Escartín in third place in the general classification, ahead of Ullrich.[129]

Before the following stage to Albertville, speculation spread that Ullrich would abandon the race.[130] Pantani's Mercatone Uno team coped well in defending his race lead over the four lesser categorised climbs, until the race reached the hors categorie final climb, the Col de la Madeleine, when Ullrich attacked, with only Pantani able to follow. Ullrich led the duo up the rest of the climb as they passed the breakaway riders and increased their advantage over the chasing Julich, who was accompanied by two teammates. The pair held their lead of around two minutes along the final 17 km (11 mi) of flat, where at the finish, Ullrich outsprinted Pantani to the stage win. Pantani now led Julich by 5:42 minutes, with Ullrich third, 14 seconds behind Julich.[131]

Another police raid on the TVM team and news about alleged mistreatment of the Festina riders while in custody led to another riders' strike on stage 17. After a brief stop of two minutes at the start, the riders rode slowly to the first intermediate sprint of the day, where they climbed off their bikes and sat on the road. Jalabert climbed into his team car and retired from the race. Meanwhile, Jean-Marie Leblanc negotiated with the riders and collected guarantees from a civil servant from the French Ministry of the Interior, who was visiting the Tour as a guest, that police treatment of the riders would improve. Nevertheless, the entire ONCE team followed their leader Jalabert and abandoned the race. As the riders slowly got moving again, they ripped off their race numbers as a further sign of protest. Luc Leblanc retired later in the stage. At the feed zone, the Banesto squad joined their fellow Spanish-based ONCE team in quitting, as did the Italian-based Riso Scotti team. The field reached the finishing town, Aix-les-Bains, two hours behind schedule. The TVM team was allowed to cross the line first as a sign of solidarity; the stage was annulled and no results counted. Overnight, two more Spanish-based teams, Kelme and Vitalicio Seguros, also decided not to carry on in the Tour. This caused the retirement of the fourth rider overall, Escartín of Kelme.[132]

Conclusion

[edit]

Before stage 18 into Neuchâtel in Switzerland, police held Massi, who was still the leader in the mountains classification, for questioning after corticoids were allegedly found in his room during a search of the Casino team hotel.[f] He was therefore unable to start the stage,[134] and the lead of the mountains classification was passed to the second placed rider, Rinero.[72] Victory went to Steels, who outsprinted Zabel and O'Grady at the finish.[134] The remaining five riders from TVM exited the race on Swiss soil before the start of the following day. Stage 19 went back into France and saw a breakaway of 13 riders. Four riders broke away from the lead group to contest the stage win between them, with Magnus Bäckstedt (GAN) coming out on top.[135]

The penultimate stage saw the last individual time trial of the race to Le Creusot. Ullrich won the stage, 1:01 minutes ahead of Julich, to move into second place overall. Pantani finished the stage third, 2:35 minutes behind Ullrich, effectively sealing his victory in the general classification.[136] The final stage on the Champs-Élysées in Paris was won by Steels from a bunch sprint, while Pantani finished safely in the peloton to secure the Tour win.[137] Ullrich ended the Tour in second place, with a deficit of 3:21 minutes, with Julich a further 47 seconds behind in third.[138] Pantani was greeted on the podium by Felice Gimondi, who had been invited by Jean-Marie Leblanc to present to the crowd the first Italian winner since his own victory in 1965.[139] Zabel won his third consecutive points classification with a total of 327, 97 ahead of O'Grady in second.[140][141] Although Pantani won two high mountain stages, the mountains classification was won by the more consistent Rinero, whose total of 200 points was 25 more than that of second-placed Pantani.[142] Due to the high number of abandons because of the Festina affair, only 96 riders reached the finish in Paris.[138] Only Team Telekom and U.S. Postal Service ended the Tour with all nine riders still racing.[143]

Doping

[edit]The prevalence of EPO in the cycling peloton had been a topic of debate since the early 1990s.[144] The first news stories about the drug appeared in 1994.[145] The UCI gave the task of developing a test for EPO to Francesco Conconi, a professor at the University of Ferrara, Italy, and a member of the UCI Medical Commission. In June 1996, Conconi, seemingly unable to find a definite test for the substance,[g] proposed to the UCI to introduce a test for an athlete's hematocrit level instead, which tested how many red cells were in a rider's blood.[146] During the UCI's meeting in Geneva, Switzerland, on 24 January 1997, the procedure, labelled as a "health test", limiting the allowed hematocrit level to 50 per cent, was introduced.[149] If a rider returned a value higher than 50 per cent, they were not allowed to compete for a two-week period. However, as cycling journalist Alasdair Fotheringham noted, "the 50 per cent threshold became a target to aim for" instead of a reliable deterrent to using EPO.[150]

The doping scandal that occurred throughout the Tour became known as the Festina affair,[151] starting with the arrest of Voet.[152] Initially, the suspicion only surrounded the Festina and TVM teams, but later investigations and retrospective tests revealed the doping abuse was far more widespread. Even while the race was running, media sources coined nicknames for it, such as the "Tour de Farce"[153][154][155] or "Tour du Dopage" (Tour of Doping).[156][157][158] Following Festina's expulsion from the race, the police investigation against the TVM team in March was made public by Le Parisien and the case reopened.[159]

Many riders in the Tour reacted to the developing scandal by hiding or destroying evidence of doping. Rolf Aldag (Team Telekom) said he flushed his doping products down the toilet before the race began in Dublin.[160] His teammate Bjarne Riis said in his autobiography that he disposed of his vials of EPO in the toilet after stage 3.[161] Likewise, the U.S. Postal team flushed their drugs down the toilet following Voet's arrest, according to Tyler Hamilton.[162] According to Jörg Jaksche, the Polti squad hid their supply of EPO in a vacuum cleaner on the team bus; Jaksche believed that most Italian teams kept their drugs during the race as well. Philippe Gaumont claimed in his autobiography that the Cofidis team were told by team management to destroy their substances on the day the Festina team was expelled, with the riders subsequently going into a forest to dispose of the evidence.[163] Julich said he quit doping altogether during the 1998 Tour.[164]

After their arrests, Voet, Roussel, and Rijckaert gave the police confessions detailed the doping practices at Festina. Roussel said that one per cent of the team's budget (around €40,000) was used to pay for EPO and human growth hormones.[165] The Festina riders were placed under custody and brought into individual prison cells, and allegedly subjected to cavity searches. On 24 July, four Festina riders confessed to taking performance-enhancing drugs, with the first being Alex Zülle. The only riders to deny the allegations were Virenque and Neil Stephens.[h][167] Examinations carried out on the nine Festina riders on 23 July, with the results being published on 28 November, revealed that eight riders took EPO and four amphetamines. Virenque was the only rider not to test positive in these tests.[168]

On 23 July, the Tour's rest day, TVM's manager Cees Priem and team doctor Andrei Mikhailov were arrested by the police.[169] At the beginning of August, team soigneur Johannes Moors was taken into custody as well.[170] Priem and Moors were released on 10 August.[171] The TVM riders were also questioned by the police on 4 August and held for about 12 hours, before they were released.[172] However, no banned substances were found during the raid at TVM's team hotel during the Tour.[173] At ONCE and BigMat, police did find performance-enhancing drugs during their raids. ONCE maintained that the substances were for medical use of the team staff.[174] Police called in twelve riders from BigMat for questioning along with the directeur sportif and some soigneurs a week after the end of the Tour because of "330 bottles and ampoules of drugs" found in the team's truck.[175]

The legal investigation into doping at the 1998 Tour was given to judge Patrick Keil shortly after the race concluded. He handed in his 5539-page report on the matter at the beginning of July 1999, which laid the groundwork for subsequent legal proceedings against team staff and riders.[176] Virenque confessed during a court hearing concerning the Festina affair, on 24 October 2000.[177] Virenque received a nine-month racing ban and a suspended prison sentence.[i] Voet was sentenced to a suspended ten months in prison and a fine of 3,000 franc. Roussell received a one-year suspended sentence and a 50,000 franc fine. Lesser verdicts were handed out to "two masseurs, the team's logistics manager, the team doctor at the Spanish ONCE team, Nicolas Terrados, and two pharmacists".[179]

During the Tour, 108 tests for performance-enhancing drugs were carried out by France's main anti-doping laboratory in Châtenay-Malabry. All of them were negative.[180][181] In 2004, 60 remaining anti-doping samples given by riders during the 1998 Tour were tested retrospectively for recombinant EPO by using three recently developed detection methods. The tests produced 44 positive results and 9 negatives, with the remaining 7 samples not returning any result due to sample degradation. At first, the rider names with a positive sample were not made public, as it had only been conducted as scientific research.[182]

In July 2013, the anti-doping committee of the French Senate decided it would benefit the current doping fight to shed full light on the past, and so decided – as part of their "Commission of Inquiry into the effectiveness of the fight against doping" report – to publish all sample IDs along with the result of the retrospective test. This revealed, that the 9 negative samples belonged to 5 riders (of whom two nevertheless had confessed using EPO in that Tour), while the 44 positive samples belonged to 33 riders – including race winner Pantani, Ullrich, Julich, and Zabel.[183][184] Julich had already admitted in 2012 that he had used EPO from August 1996 to July 1998.[185]

Classification leadership and minor prizes

[edit]

There were several classifications in the 1998 Tour de France.[186] The most important was the general classification, calculated by adding each cyclist's finishing times on each stage. The cyclist with the least accumulated time was the race leader, identified by the yellow jersey; the winner of this classification is considered the winner of the Tour.[187] Jan Ullrich wore the yellow jersey in the prologue as the winner of the previous edition.[70] Time bonuses were given during the first half of the Tour to the first three finishers on each stage, excluding mountain stages and time trials. The winner received a 20-second bonus, the second finisher 12 seconds and the third rider 8 seconds.[188] During the first half of the race, intermediate sprints also had time bonuses, with bonuses of 6, 4, and 2 seconds given to the first three riders to cross the line.[189]

Additionally, there was a points classification, in which cyclists got points for finishing among the best in a stage finish, or in intermediate sprints.[190] In flat stages, the first 25 finishers received points, 35 for the stage winner down to 1 point for 25th place. In medium mountain stages, the top-20 finishers received points, with 25 points for the stage winner down to 1 point. In mountain stages, the first 15 finishers received points, with 20 points given to the stage winner. In time trials, 15 points were given to the winner, down to 1 point for the tenth-placed finisher.[191] Points could also be won during intermediate sprints along the race route, with 6, 4, and 2 points for the first three riders across the line respectively.[192] The cyclist with the most points led the classification, and was identified by a green jersey.[190]

There was also a mountains classification. Most stages of the race included one or more categorised climbs, in which points were awarded to the riders that reached the summit first. The climbs were categorised as fourth-, third-, second- or first-category and hors catégorie, with the more difficult climbs rated lower.[193] The first rider to cross the summit of an hors catégorie climb was given 40 points (down to 1 point for the 15th rider). Twelve riders received points for first category climbs, with 30 for the first rider to reach the summit. Second-, third- and fourth-category climbs gave 20, 10 and 5 points to the first rider respectively.[194] The cyclist with the most points led the classification, wearing a white jersey with red polka dots.[193]

The young rider classification, which was not marked by a jersey, was decided the same way as the general classification, but only riders under 26 years were eligible.[195] This meant that in order to compete in the classification, a rider had to be born after 1 January 1973. 34 out of the 189 starters were eligible.[196] Jan Ullrich won the classification for the third time in a row.[197]

For the team classification, the times of the best three cyclists per team on each stage were added; the leading team was the team with the lowest total time.[198]

In addition, there was a combativity award given after each mass-start stage to the cyclist considered the most combative. The winner of the award wore a red number bib during the next stage, this feature was introduced for the first time in 1998. The decision was made by a jury composed of journalists who gave points. The cyclist with the most points from votes in all stages led the combativity classification.[199][198] Jacky Durand won this classification, and was given overall the super-combativity award.[45] The Souvenir Henri Desgrange was given in honour of Tour founder Henri Desgrange to the first rider to pass the summit of the Col du Galibier on stage 15. The winner of the prize was Marco Pantani.[48]

- In stage one, Abraham Olano, who was second in the points classification, wore the green jersey, because first placed Chris Boardman wore the yellow jersey as leader of the general classification.[202][203]

Final standings

[edit]| Legend | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Denotes the winner of the general classification | Denotes the winner of the points classification | ||

| Denotes the winner of the mountains classification | Denotes the winner of the super-combativity award | ||

General classification

[edit]| Rank | Rider | Team | Time |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Mercatone Uno–Bianchi | 92h 49' 46" | |

| 2 | Team Telekom | + 3' 21" | |

| 3 | Cofidis | + 4' 08" | |

| 4 | Cofidis | + 9' 16" | |

| 5 | Rabobank | + 11' 26" | |

| 6 | U.S. Postal Service | + 14' 57" | |

| 7 | Cofidis | + 15' 13" | |

| 8 | Mapei–Bricobi | + 16' 07" | |

| 9 | Mapei–Bricobi | + 17' 35" | |

| 10 | Team Polti | + 17' 39" |

Points classification

[edit]| Rank | Rider | Team | Points |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Team Telekom | 327 | |

| 2 | GAN | 230 | |

| 3 | Mapei–Bricobi | 221 | |

| 4 | Rabobank | 196 | |

| 5 | U.S. Postal Service | 151 | |

| 6 | GAN | 149 | |

| 7 | Cofidis | 114 | |

| 8 | Casino–Ag2r | 111 | |

| 9 | Asics–CGA | 99 | |

| 10 | Mercatone Uno–Bianchi | 90 |

Mountains classification

[edit]| Rank | Rider | Team | Points |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Cofidis | 200 | |

| 2 | Mercatone Uno–Bianchi | 175 | |

| 3 | Casino–Ag2r | 165 | |

| 4 | GAN | 156 | |

| 5 | Française des Jeux | 152 | |

| 6 | Team Telekom | 126 | |

| 7 | Cofidis | 98 | |

| 8 | Rabobank | 92 | |

| 9 | Saeco–Cannondale | 90 | |

| 10 | Cofidis | 89 |

Young rider classification

[edit]| Rank | Rider | Team | Time |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Team Telekom | 92h 53' 07" | |

| 2 | Cofidis | + 5' 55" | |

| 3 | Mapei–Bricobi | + 14' 14" | |

| 4 | Cofidis | + 30' 42" | |

| 5 | Team Polti | + 32' 20" | |

| 6 | Lotto–Mobistar | + 38' 02" | |

| 7 | Lotto–Mobistar | + 47' 57" | |

| 8 | Rabobank | + 1h 26' 16" | |

| 9 | Team Polti | + 1h 28' 32" | |

| 10 | Cofidis | + 1h 35' 24" |

Team classification

[edit]| Rank | Team | Time |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | Cofidis | 278h 29' 58" |

| 2 | Casino–Ag2r | + 29' 09" |

| 3 | U.S. Postal Service | + 41' 40" |

| 4 | Team Telekom | + 46' 01" |

| 5 | Lotto–Mobistar | + 1h 04' 14" |

| 6 | Team Polti | + 1h 06' 32" |

| 7 | Rabobank | + 1h 46' 20" |

| 8 | Mapei–Bricobi | + 1h 59' 53" |

| 9 | BigMat–Auber 93 | + 2h 03' 32" |

| 10 | Mercatone Uno–Bianchi | + 2h 23' 04" |

Combativity classification

[edit]| Rank | Rider | Team | Points |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Casino–Ag2r | 94 | |

| 2 | Mapei–Bricobi | 51 | |

| 3 | Française des Jeux | 49 | |

| 4 | GAN | 47 | |

| 5 | Casino–Ag2r | 43 | |

| 6 | Cofidis | 35 | |

| 7 | Asics–CGA | 33 | |

| 8 | BigMat–Auber 93 | 30 | |

| 9 | Cofidis | 28 | |

| 10 | Casino–Ag2r | 28 |

UCI Road Rankings

[edit]Riders in the Tour competed individually, as well as for their teams and nations, for points that contributed towards the UCI Road Rankings, which included all UCI races.[207] Points were awarded to all riders in the general classification, to the top ten finishers in each stage, and each yellow jersey given at the end of a stage.[208] The points accrued by Marco Pantani moved him from fifth position to fourth in the individual ranking, with Laurent Jalabert, who did not finish the Tour, holding his lead. Festina–Lotus retained their lead of the team ranking, ahead of second-placed Mapei–Bricobi. Italy remained as leaders of the nations ranking, with Switzerland second.[209]

| Rank | Prev. | Name | Team | Points |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 1 | ONCE | 2961.00 | |

| 2 | 2 | Festina–Lotus | 2196.00 | |

| 3 | 3 | Asics–CGA | 2097.00 | |

| 4 | 5 | Mercatone Uno–Bianchi | 1961.00 | |

| 5 | 4 | Festina–Lotus | 1535.80 | |

| 6 | 7 | Lotto–Mobistar | 1400.00 | |

| 7 | 9 | Team Polti | 1301.00 | |

| 8 | 8 | Cofidis | 1290.00 | |

| 9 | 12 | Mapei–Bricobi | 1281.50 | |

| 10 | 16 | Rabobank | 1279.00 |

Aftermath

[edit]If we hadn't had those scandals, the Festina affair and so on, we would have continued in the world of ignorance and supposition. This way, [doping] was smashed right into our face.

In the direct aftermath of the Tour, there were many raids and searches of cycling teams and many riders questioned by police.[k] Two meetings to discuss the issue of doping were held shortly after the Tour: the first, between the UCI, race organisers and teams, took place four days after the Tour ended in Paris; the second, on 11 August, was between the UCI and representatives of the riders. Neither meeting yielded results that had "any long-term effect".[211] The riders voiced concern over the length of races and demanded changes to be made, while the question of a general amnesty for riders who took banned substances was also briefly discussed.[212] In a press communiqué released on 13 August, the UCI claimed that "it is difficult to do more than is already being done" in response to doping and that the blood tests enforced in 1997 enabled the UCI "to control the EPO problem", a claim that Alasdair Fotheringham later described as bordering "on the delusional".[213]

Festina returned to racing shortly after the Tour de France, with the crowd showing positive responses to the team at the Vuelta a Burgos. The squad then competed in the last Grand Tour of the year, the Vuelta a España,[214] where Alex Zülle failed to defend his title, but won a stage and finished eighth overall.[215]

Following the fallout from the 1998 edition, the 1999 Tour de France was dubbed by the organisers as the "Tour of Renewal", with the ASO publicly stating that they would welcome a lower average speed by around 3 km/h (1.9 mph).[216] This did not come to pass however, as the average speed rose again[216] and race winner Lance Armstrong was stripped of his title in 2012 following a lengthy investigation into doping practises.[217] ASO barred the TVM team from competing in the 1999 race.[218] Richard Virenque and Manolo Saiz were originally banned from the race, before the UCI required the race organisers to allow both to participate, considering that the ASO had failed to comply with the registration period. This dictates that both organisers and teams need to register the invitation and their willingness to participate thirty days before the start of the event.[216] Festina was allowed to start the next Tour, but the ASO handed out a warning to the team before the race, reminding them of their ability to disqualify them as they had in 1998.[219]

The Tour de France scandal highlighted the need for an independent international agency that would set harmonized standards for anti-doping work and coordinate the efforts of sports organizations and public authorities.

Fotheringham noted nearly twenty years after the 1998 Tour that ever since, extraordinary performances in cycling have been viewed with suspicion, because of the sport's now cemented association with doping. Until the revelations of the Lance Armstrong doping case, the 1998 Tour de France stood as the biggest doping scandal in sport.[221] One of the most significant effects of the Festina affair was the creation of the World Anti-Doping Agency (WADA) in December 1999.[222]

In the media

[edit]In 2018, a film centering around the 1998 Tour, titled The Domestique and to be directed by Kieron J. Walsh and written by Ciarán Cassidy, was announced. Production was taken over by Blinder Films, with the movie receiving €800,000 funding through Screen Ireland, the Irish state development agency.[223] The film has since been renamed The Racer and secured funding from Screen Flanders, the Film Fund Luxembourg, Eurimages, the BAI Sound & Vision Fund, and RTÉ.[224] The film premiered at the 2020 South by Southwest film festival.[225]

See also

[edit]- 1998 in sports

- List of doping cases in cycling

- Operación Puerto doping case – a Spanish Police operation against mainly doping in professional cycling that began in 2006

Notes

[edit]- ^ Stage 12 was originally scheduled to be 206 km (128 mi) long, but as a result of the delayed start due to a riders' strike, the stage was shortened to 190 km (118 mi).[58]

- ^ a b c Stage 17 was cancelled and did not count as the riders held a strike due to the developing Festina affair.[59]

- ^ The content of Voet's car was "82 vials of Saizen (somatropin, or human growth hormone), 60 capsules of Pantestone (epitestosterone), 248 vials of physiological serum, 8 pre-filled syringes containing hepatitis-A vaccine, 2 boxes of 30 Hyperlipen tablets (to lower the amount of fat in the blood), 4 further doses of somatropin, 4 ampoules of Synacthene (to increase the rate at which corticoid hormones are secreted by the adrenal gland) and 2 vials of amphetamine" as well as "234 doses of recombinant human erythropoietin".[65]

- ^ Common cycling tactics dictate that riders should stay towards the front of the peloton to minimise the risk of being involved in a crash.[77]

- ^ Over the course of his career, Mario Cipollini had shown a tendency to avoid riding high mountain stages, which did not suit him, instead focusing on the flat stages in the first week of the race. In fact, he never finished a Tour de France in seven appearances, neither the Vuelta a España in six attempts.[100]

- ^ Massi was later cleared of all charges.[133]

- ^ Around the year 2000, investigations in Italy revealed that Conconi had used the money given to him by the UCI to provide EPO to professional cyclists.[146][147] A promising test for EPO by Canadian scientist Guy Brisson, who conducted a trial run during the 1996 Tour de Suisse and found indications of EPO abuse in all tested 77 riders, was not followed up by the UCI, due to fear that the test would not "stand up to legal challenges".[148]

- ^ Stephens maintains that he took EPO unknowingly, having thought it to be vitamin supplements.[166]

- ^ Virenque appealed the decision at the Court of Arbitration for Sport in Lausanne, Switzerland. The Court considered turning his ban into a suspended sentence. They eventually upheld the verdict, but brought its start date forward, meaning Virenque was able to return to competition on 14 August 2001.[178]

- ^ A white jersey was not awarded to the leader of the young rider classification between 1989 and 1999.[195]

- ^ The Cantina Tollo team vehicles were searched upon entering Spain for the Clásica de San Sebastián, while Française des Jeux had their cars searched when entering Germany to compete at the Regio-Tour. Meanwhile, Peter van Petegem, a member of TVM, was called in to testify towards the suspicious exit of his former team PDM–Concorde–Ultima during the 1991 Tour de France, when Eric Ryckaert was working there as a team doctor.[171]

References

[edit]- ^ a b c d "Ullrich enthousiast, Virenque in mineur" [Ullrich enthusiastic, Virenque in minor]. De Volkskrant (in Dutch). 24 October 1997. Archived from the original on 16 April 2019. Retrieved 16 April 2019.

- ^ a b c "1998 Tour de France – Sporting aspects". Tour de France. Amaury Sport Organisation. Archived from the original on 26 May 1998. Retrieved 24 March 2019.

- ^ "News for February 6, 1998: Tour 1998". Cyclingnews.com. 6 February 1998. Archived from the original on 25 October 2012. Retrieved 21 August 2011.

- ^ "News for June 19, 1998: In the Tour de France". Cyclingnews.com. 19 June 1998. Archived from the original on 25 October 2012. Retrieved 21 August 2011.

- ^ Edwards et al. 1998, p. 30.

- ^ a b c "Le Tour de France report – Teams". Union Cycliste Internationale. Archived from the original on 16 May 2019. Retrieved 16 May 2019.

- ^ "Tour de France 1998 – Debutants". ProCyclingStats. Archived from the original on 12 May 2019. Retrieved 12 May 2019.

- ^ "Tour de France 1998 – Youngest competitors". ProCyclingStats. Archived from the original on 12 May 2019. Retrieved 12 May 2019.

- ^ "Tour de France 1998 – Average team age". ProCyclingStats. Archived from the original on 12 May 2019. Retrieved 12 May 2019.

- ^ Augendre 2016, p. 113.

- ^ Fotheringham 2017, p. 5.

- ^ Whittle et al. 1998, p. 77.

- ^ a b Fotheringham 2017, p. 6.

- ^ a b c McGann & McGann 2008, p. 243.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i Kelly, Seamus. "Le Tour de France report – Intro". Union Cycliste Internationale. Archived from the original on 5 June 2019. Retrieved 5 June 2019.

- ^ a b Arribas, Carlos (16 March 1998). "Ullrich está gordo" [Ullrich is fat]. El País (in Spanish). Archived from the original on 16 April 2019. Retrieved 16 April 2019.

- ^ a b c d e f g Abt, Samuel (7 July 1998). "Cycling; Ullrich ready to roll after tasting success". The New York Times. Archived from the original on 16 April 2019. Retrieved 16 April 2019.

- ^ Fotheringham 2017, pp. 5–6.

- ^ a b Moore 2014, p. 181.

- ^ Arribas, Carlos (11 July 1998). "Ullrich y los demás" [Ullrich and the others]. El País (in Spanish). Archived from the original on 16 April 2019. Retrieved 16 April 2019.

- ^ a b "UCI Road Rankings – 7 July 1998" (PDF). Union Cycliste Internationale. 7 July 1998. Archived from the original (PDF) on 30 August 2000. Retrieved 6 May 2019.

- ^ Augendre 2016, p. 120.

- ^ Fotheringham 2017, pp. 6–7.

- ^ Whittle et al. 1998, p. 26.

- ^ a b Whittle et al. 1998, pp. 28–28.

- ^ a b Farrand, Stephen (26 April 2018). "Giro d'Italia: The apotheosis of Marco Pantani". Cyclingnews.com. Archived from the original on 16 April 2019. Retrieved 16 April 2019.

- ^ "Giro d'Italia, Grand Tour – Stage 22 brief". Cyclingnews.com. 7 June 1998. Archived from the original on 6 June 2019. Retrieved 13 May 2019.

- ^ a b Fotheringham 2017, p. 7.

- ^ a b Whittle et al. 1998, p. 36.

- ^ Friebe 2014, pp. 144–146.

- ^ a b c d e Whittle et al. 1998, p. 34.

- ^ Augendre 2016, p. 110.

- ^ Whittle et al. 1998, p. 29.

- ^ Whittle et al. 1998, pp. 40–44.

- ^ a b "The Tour de France". The Irish Times. 24 October 1997. Archived from the original on 18 June 2019. Retrieved 16 April 2019.

- ^ a b Abt, Samuel (24 October 1997). "Cycling: Tour de France; 1998 race too flat for Virenque's tastes". The New York Times. Archived from the original on 16 April 2019. Retrieved 16 April 2019.

- ^ Dunne, Jim (9 October 1996). "Ireland may host start of 1998 Tour de France". The Irish Times. Archived from the original on 18 June 2019. Retrieved 16 April 2019.

- ^ McArdle, Jim (3 April 1997). "Irish stages confirmed for 1998 Tour de France". The Irish Times. Archived from the original on 18 June 2019. Retrieved 16 April 2019.

- ^ Dunne, Jim (4 April 1997). "Tour worth £30m to economy – Kenny". The Irish Times. Archived from the original on 18 June 2019. Retrieved 16 April 2019.

- ^ O'Brien, Tim (11 July 1998). "Service commemorates Shay Elliott". The Irish Times. Archived from the original on 18 June 2019. Retrieved 9 May 2019.

- ^ Smith 2009, p. 148.

- ^ Watterson, Johnny (14 July 1998). "Race whizzes through Carrick in tribute to a great Irish sportsman". The Irish Times. Archived from the original on 18 June 2019. Retrieved 9 May 2019.

- ^ Smith 2009, p. 147.

- ^ Rendell 2007, p. 116.

- ^ a b c Augendre 2016, p. 89.

- ^ a b c "Le Tour de France report". Union Cycliste Internationale. Archived from the original on 16 May 2019. Retrieved 16 May 2019.

- ^ Augendre 2016, pp. 177–178.

- ^ a b "Tour de France, Grand Tour – Stage 15 brief". Cyclingnews.com. 27 July 1998. Archived from the original on 9 September 2011. Retrieved 13 May 2019.

- ^ "Le Tour de France report – Stage 10". Union Cycliste Internationale. Archived from the original on 16 May 2019. Retrieved 16 May 2019.

- ^ "Le Tour de France report – Stage 11". Union Cycliste Internationale. Archived from the original on 16 May 2019. Retrieved 16 May 2019.

- ^ "Le Tour de France report – Stage 15". Union Cycliste Internationale. Archived from the original on 16 May 2019. Retrieved 16 May 2019.

- ^ "Le Tour de France report – Stage 16". Union Cycliste Internationale. Archived from the original on 16 May 2019. Retrieved 16 May 2019.

- ^ a b Edwards et al. 1998, p. 43.

- ^ a b Edwards et al. 1998, p. 51.

- ^ van den Akker 2018, p. 12.

- ^ a b Bacon 2014, p. 210.

- ^ "The history of the Tour de France – Year 1998 – The stage winners". Tour de France. Amaury Sport Organisation. Archived from the original on 3 April 2020. Retrieved 4 April 2020.

- ^ Fotheringham 2017, p. 142.

- ^ "Stage 17 cancelled". Tour de France. Amaury Sport Organisation. Archived from the original on 3 February 1999. Retrieved 24 March 2019.

- ^ Edwards et al. 1998, p. 2.

- ^ Edwards et al. 1998, p. 12.

- ^ "Dauphiné Libéré: De las Cuevas leader". La Dépêche du Midi (in French). 11 June 1998. Retrieved 16 August 2019.

- ^ Woodland 2003, p. 155.

- ^ a b Edwards et al. 1998, p. 1.

- ^ a b Rendell 2007, p. 117.

- ^ a b c d Edwards et al. 1998, p. 19.

- ^ Abt, Samuel (12 July 1998). "Cycling; Boardman wins as drug case arises". The New York Times. Archived from the original on 12 May 2019. Retrieved 12 May 2019.

- ^ McGann & McGann 2008, p. 246.

- ^ a b Edwards et al. 1998, p. 31.

- ^ a b Edwards et al. 1998, p. 27.

- ^ a b Rendell 2007, p. 118.

- ^ a b c d e f "Tour de France 1998 – Leaders overview". ProCyclingStats. Archived from the original on 16 February 2019. Retrieved 16 February 2019.

- ^ Edwards et al. 1998, p. 35.

- ^ Willoughby, Roy (reporter) (12 July 1998). "Wicklow Welcomes Tour de France". Sunday Sport. RTÉ Sport. Archived from the original on 29 May 2019. Retrieved 10 June 2019.

- ^ Edwards et al. 1998, p. 33.

- ^ Edwards et al. 1998, pp. 34–35.

- ^ Friebe 2014, p. 148.

- ^ Edwards et al. 1998, pp. 39–40.

- ^ Friebe 2014, p. 142.

- ^ Pogatchnik, Shawn (13 July 1998). "Britain's Boardman out of Tour after crash". The Washington Post. Associated Press. Archived from the original on 18 June 2019. Retrieved 12 May 2019.

- ^ Edwards et al. 1998, pp. 42–43.

- ^ Edwards et al. 1998, p. 38.

- ^ Edwards et al. 1998, pp. 40–41.

- ^ Edwards et al. 1998, pp. 47–52.

- ^ Edwards et al. 1998, pp. 52–53.

- ^ Fotheringham 2017, p. 77.

- ^ Edwards et al. 1998, pp. 55–60.

- ^ Edwards et al. 1998, p. 58.

- ^ Fotheringham 2017, p. 81.

- ^ Fotheringham 2017, p. 79.

- ^ Edwards et al. 1998, p. 67 & 72.

- ^ Edwards et al. 1998, p. 74.

- ^ Edwards et al. 1998, p. 64.

- ^ McGann & McGann 2008, pp. 246–247.

- ^ Fife 2000, p. 202.

- ^ Edwards et al. 1998, pp. 77–84.

- ^ Edwards et al. 1998, pp. 85–91.

- ^ "Tour de France, Grand Tour – Stage 9 brief". Cyclingnews.com. 20 July 1998. Archived from the original on 1 July 2012. Retrieved 13 June 2019.

- ^ Fotheringham 2017, p. 116.

- ^ Abt, Samuel (9 September 2003). "Cycling: Hardly a sprint, but Cipollini heads toward the end". The New York Times. Archived from the original on 9 March 2020. Retrieved 9 March 2020.

- ^ Edwards et al. 1998, pp. 100.

- ^ a b c "Casino gamble pays great dividends". Tour de France. Amaury Sport Organisation. Archived from the original on 12 December 2004. Retrieved 14 June 2019.

- ^ Edwards et al. 1998, p. 99.

- ^ Edwards et al. 1998, pp. 99–106.

- ^ Edwards et al. 1998, pp. 105–106.

- ^ Nicholl, Robin (16 July 1997). "Ullrich produces a tour de force". The Independent. Archived from the original on 18 June 2019. Retrieved 14 June 2019.

- ^ Longmore, Andrew (27 June 1999). "Tour de France: From quiet American to big noise". The Independent. Archived from the original on 18 June 2019. Retrieved 14 June 2019.

- ^ Edwards et al. 1998, pp. 108–112.

- ^ Friebe 2014, p. 153.

- ^ Edwards et al. 1998, pp. 112–113.

- ^ Edwards et al. 1998, p. 108.

- ^ Fotheringham 2017, p. 138.

- ^ a b Edwards et al. 1998, p. 118.

- ^ Fotheringham 2017, pp. 139–140.

- ^ a b Fotheringham, William (25 July 1998). "Jalabert Puts on a Show with Road Rage". The Guardian. p. 35. Retrieved 9 May 2020.

- ^ a b Gómez, Luis (25 July 1998). "Escapada simbólica de Jalabert" [Symbolic Escape by Jalabert]. El País (in Spanish). Retrieved 9 May 2020.

- ^ Fotheringham 2017, pp. 141–143.

- ^ Edwards et al. 1998, pp. 119–121.

- ^ Edwards et al. 1998, pp. 119–122.

- ^ Fotheringham 2017, p. 143.

- ^ Fotheringham 2017, p. 152.

- ^ a b "Tour de France, Grand Tour – Stage 14 brief". Cyclingnews.com. 26 July 1998. Archived from the original on 22 March 2016. Retrieved 17 June 2019.

- ^ Edwards et al. 1998, pp. 134–135.

- ^ Fotheringham 2017, p. 164.

- ^ Fotheringham 2017, p. 165.

- ^ Fotheringham 2017, p. 166.

- ^ Edwards et al. 1998, p. 141.

- ^ Rendell 2007, pp. 124–126.

- ^ Edwards et al. 1998, pp. 142–146.

- ^ Fotheringham 2017, p. 187.

- ^ Edwards et al. 1998, pp. 147–152.

- ^ Fotheringham 2017, pp. 202–223.

- ^ "'Festina Affair': A timeline". BBC Sport. 24 October 2000. Retrieved 30 October 2019.

- ^ a b Thomazeau, François (30 July 1998). "Troubled Tour Resumes; Steels Wins 18th Stage". The Washington Post. Reuters. Archived from the original on 4 June 2019. Retrieved 4 June 2019.

- ^ Abt, Samuel (1 August 1998). "Backstedt's Late Surge Gives Him Slim Victory". The New York Times. Archived from the original on 27 May 2015. Retrieved 4 June 2019.

- ^ Edwards et al. 1998, pp. 174–175.

- ^ Edwards et al. 1998, p. 177.

- ^ a b c d "Stage 21: Melun – Paris-Champs-Élysées (147,5 km): Overall standings". Tour de France. Amaury Sport Organisation. Archived from the original on 21 December 1999. Retrieved 23 March 2019.

- ^ Westemeyer, Susan (5 February 2007). "Gimondi on Pantani film and cyclist". Cyclingnews.com. Retrieved 19 August 2019.

- ^ Augendre 2016, p. 119.

- ^ a b "Stage 21: Melun – Paris-Champs-Élysées (147,5 km): Overall sprinters". Tour de France. Amaury Sport Organisation. Archived from the original on 21 December 1999. Retrieved 23 March 2019.

- ^ a b "Stage 21: Melun – Paris-Champs-Élysées (147,5 km): Overall climbers". Tour de France. Amaury Sport Organisation. Archived from the original on 21 December 1999. Retrieved 23 March 2019.

- ^ van den Akker 2018, p. 39.

- ^ Woodland 2003, p. 142.

- ^ Fotheringham 2017, p. 106.

- ^ a b Fotheringham 2017, p. 109.

- ^ Capodacqua, Eugenio (27 October 2000). "Ecco il doping di Conconi" [Here is the doping of Conconi]. la Repubblica (in Italian). Archived from the original on 30 October 2019. Retrieved 30 October 2019.

- ^ Fotheringham 2017, pp. 112–113.

- ^ Martin, Daniel T.; Ashenden, Michael; Parisotto, Robin; Pyne, David; Hahn, Allan G. (1997). "Blood Testing for Professional Cyclists: What's a fair hematocrit limit?". sportsci.org. Sportscience News. Retrieved 16 August 2019.

- ^ Fotheringham 2017, p. 107.

- ^ Whittle, Jeremy (3 March 2017). "The 1998 Tour de France: Police raids, arrests, protests... and a bike race". Cyclingnews.com. Retrieved 25 June 2019.

- ^ "Tour rocked by drugs arrest". BBC News. 11 July 1998. Retrieved 25 June 2019.

- ^ Fotheringham 2017, p. Dust jacket.

- ^ Fotheringham, William (28 January 2004). "Scandal revives doping fears". TheGuardian.com. Archived from the original on 18 June 2019. Retrieved 18 June 2019.

- ^ "Ausblenden und Gesundbeten" [Suppressing and Healing Through Faith]. Der Spiegel (in German). No. 31/1998. p. 104. Archived from the original on 22 February 2011. Retrieved 4 June 2019.

- ^ "De positieve renners van de Tour du dopage" [The positive riders of the Tour du Dopage]. de Volkskrant (in Dutch). 24 July 2013. Retrieved 25 June 2019.

- ^ "Radsport: TVM-Affäre 1998: Blijlevens und Voskamp gestehen Epo-Doping" [TVM affair: Blijlevens and Voskamp admit to EPO doping]. Focus (in German). Sport-Informations-Dienst. 11 July 2014. Retrieved 25 June 2019.

- ^ Waddington 2001, p. 159.

- ^ Fotheringham 2017, p. 96.

- ^ Fotheringham 2017, p. 1.

- ^ Riis & Pedersen 2012, p. 171.

- ^ Fotheringham 2017, p. 92.

- ^ Fotheringham 2017, pp. 60–61.

- ^ Fotheringham 2017, p. 279.

- ^ Fotheringham 2017, p. 71.

- ^ Aubrey, Jane (12 December 2012). "Orica-GreenEdge owner unaware of Stephens' past admissions". Cyclingnews.com. Retrieved 16 August 2019.

- ^ Fotheringham 2017, pp. 135–138.

- ^ "News for October 25, 2000". Cyclingnews.com. 25 October 2000. Retrieved 2 September 2019.

- ^ Fotheringham 2017, p. 135.

- ^ "News for August 4, 1998: The drugs scandal update". Cyclingnews.com. 4 August 1998. Retrieved 5 September 2019.

- ^ a b "News for August 11, 1998: Drugs Scandal update". Cyclingnews.com. 11 August 1998. Retrieved 5 September 2019.

- ^ "Second Edition News for August 4, 1998: The drugs scandal update". Cyclingnews.com. 4 August 1998. Retrieved 5 September 2019.

- ^ "News for August 8, 1998: The drugs scandal update". Cyclingnews.com. 8 August 1998. Retrieved 5 September 2019.

- ^ "News for August 4, 1998: The drugs scandal update". Cyclingnews.com. 4 August 1998. Retrieved 5 September 2019.

- ^ "News for August 15, 1998: Drugs Update". Cyclingnews.com. 15 August 1998. Retrieved 5 September 2019.

- ^ "News for July 2, 1999". Cyclingnews.com. 2 July 1999. Retrieved 2 September 2019.

- ^ Hamoir, Oliver (25 October 2000). "Virenque: 'I took drugs, I had no choice'". The Independent. Archived from the original on 1 May 2022. Retrieved 16 August 2019.

- ^ "News for March 13, 2001: Virenque's suspension brought forward". Cyclingnews.com. 13 March 2001. Retrieved 5 September 2019.

- ^ Fotheringham, William (23 December 2000). "Festina trial ends with fines and a warning". The Guardian. Retrieved 2 September 2019.

- ^ Fotheringham 2017, p. 101.

- ^ Waddington & Smith 2009, p. 148.

- ^ "1998 plane sur le centième Tour de France" [1998 flat on the hundredth Tour de France]. La Dernière Heure (in French). 27 June 2013. Archived from the original on 30 June 2013. Retrieved 28 July 2013.

- ^ "Cipollini, Livingston among 1998 Tour riders positive for EPO". VeloNews. 24 July 2013. Archived from the original on 28 July 2013. Retrieved 28 July 2013.

- ^ "Rapport Fait au nom de la commission d'enquête sur l'efficacité de la lutte contre le dopage (Annexe 6: Résultats test EPO Tour De France 1998 et 1999)" [Report Made on behalf of the commission of inquiry into the effectiveness of the fight against doping (Appendix 6: EPO test results Tour de France 1998 and 1999)] (PDF). N° 782, Sénat Session Extraordinaire de 2012–2013 (in French). French Senate. 17 July 2013. Archived (PDF) from the original on 6 August 2013. Retrieved 28 July 2013.

- ^ "Exclusive: Bobby Julich doping confession". Cyclingnews.com. 25 October 2012. Archived from the original on 25 October 2012. Retrieved 25 October 2012.

- ^ Nauright & Parrish 2012, pp. 452–455.

- ^ Nauright & Parrish 2012, pp. 452–453.

- ^ van den Akker 2018, pp. 128–129.

- ^ van den Akker 2018, p. 183.

- ^ a b Nauright & Parrish 2012, pp. 453–454.

- ^ van den Akker 2018, p. 154.

- ^ van den Akker 2018, p. 182.

- ^ a b Nauright & Parrish 2012, p. 454.

- ^ van den Akker 2018, p. 164.

- ^ a b Nauright & Parrish 2012, pp. 454–455.

- ^ van den Akker 2018, pp. 174–175.

- ^ van den Akker 2018, p. 176.

- ^ a b Nauright & Parrish 2012, p. 455.

- ^ van den Akker 2018, pp. 211–216.

- ^ "Tour de France 1998 – Leaders overview". ProCyclingStats. Archived from the original on 16 February 2019. Retrieved 16 February 2019.

- ^ van den Akker, Pieter. "Informatie over de Tour de France van 1998" [Information about the Tour de France from 1998]. TourDeFranceStatistieken.nl (in Dutch). Archived from the original on 2 March 2019. Retrieved 2 March 2019.

- ^ "Stage 1: Dublin – Dublin (180,5 km): Overall standings". Tour de France. Amaury Sport Organisation. Archived from the original on 25 October 2000. Retrieved 24 March 2019.

- ^ "Stage 1: Dublin – Dublin (180,5 km): Overall sprinters". Tour de France. Amaury Sport Organisation. Archived from the original on 25 October 2000. Retrieved 24 March 2019.

- ^ "Stage 21: Melun – Paris-Champs-Élysées (147,5 km): Overall youth". Tour de France. Amaury Sport Organisation. Archived from the original on 7 March 2000. Retrieved 10 September 2016.

- ^ "Stage 21: Melun – Paris-Champs-Élysées (147,5 km): Overall team". Tour de France. Amaury Sport Organisation. Archived from the original on 25 December 1999. Retrieved 23 March 2019.

- ^ "Stage 21: Melun – Paris-Champs-Élysées (147,5 km): Overall combativity". Tour de France. Amaury Sport Organisation. Archived from the original on 25 December 1999. Retrieved 10 September 2016.

- ^ UCI Rules 1998, pp. 107–108.

- ^ UCI Rules 1998, pp. 108–109.

- ^ a b "UCI Road Rankings – 2 August 1998" (PDF). Union Cycliste Internationale. 3 August 1998. Archived from the original (PDF) on 30 August 2000. Retrieved 24 March 2019.

- ^ Fotheringham 2017, p. 264.

- ^ Fotheringham 2017, pp. 272–273.

- ^ "Second Edition News for August 12, 1998: Drugs Update". Cyclingnews.com. 12 August 1998. Retrieved 5 September 2019.

- ^ Fotheringham 2017, pp. 273–275.

- ^ "Festina to turn the page". Cyclingnews.com. 4 September 1998. Retrieved 31 August 2019.

- ^ "Año 1998". LaVuelta.es (in Spanish). Unipublic. Archived from the original on 18 August 2017. Retrieved 31 August 2019.

- ^ a b c Quénet, Jean-François (27 June 2019). "1999 Tour de France: The farce of renewal". Cyclingnews.com. Retrieved 2 September 2019.

- ^ Macur, Juliet (22 October 2012). "Lance Armstrong Is Stripped of His 7 Tour de France Titles". The New York Times. Retrieved 2 September 2019.

- ^ "News for June 17, 1999". Cyclingnews.com. 17 June 1999. Retrieved 2 September 2019.

- ^ Fotheringham 2017, p. 282.

- ^ "1990s – A New Agency for a New Mission" (PDF). Play True (2): 29. 2009. Retrieved 6 September 2019.

- ^ Fotheringham 2017, pp. 269–270.

- ^ Fotheringham 2017, p. 271.

- ^ Shortall, Eithne (22 July 2018). "Tour de Dopage film The Domestique passes test for Screen Ireland funding". The Times. Archived from the original on 31 July 2018. Retrieved 12 June 2019.

- ^ Clarke, Stewart (29 July 2019). "First Look at 1998 Tour de France Film 'The Racer'". Variety. Retrieved 4 November 2019.

- ^ "Irish Tour de France drama The Racer will receive World Premiere at SXSW in March". Fís Éireann. 16 January 2020. Retrieved 26 February 2021.

Bibliography

[edit]- Augendre, Jacques (2016). "Guide historique" [Historical guide] (PDF). Tour de France (in French). Paris: Amaury Sport Organisation. Archived (PDF) from the original on 17 August 2016. Retrieved 27 October 2016.

- Bacon, Ellis (2014). Mapping Le Tour: Updated History and Route Map of Every Tour de France Race. Glasgow, UK: HarperCollins. ISBN 978-0-00-754399-1.

- Edwards, Beth; Hobkirk, Lori; Jew, Bryan; Johnson, Tim; Mikler, Kip; Neshama, Rivvy; Pelkey, Charles; Rezell, John; Wilcockson, John; Wood, Steve; Zinn, Lennard (1998). Conquests and Crisis: The 1998 Tour de France. Featuring the Tour diaries of Frankie Andreu. Boulder, Colorado: VeloPress. ISBN 978-1-884737-65-7.

- Fife, Graeme (2000). Tour de France: The History, the Legend, the Riders. Edinburgh: Mainstream Publishing. ISBN 978-1-84018-284-2.

- Fotheringham, Alasdair (2017). The End of the Road: The Festina Affair and the Tour that Almost Wrecked Cycling. London: Bloomsbury Publishing. ISBN 978-1-4729-1304-3.

- Friebe, Daniel (2014), "Il Pirata", in Bacon, Ellis; Birnie, Lionel (eds.), The Cycling Anthology, vol. 4, London: Yellow Jersey Press, pp. 141–165, ISBN 978-0-2240-9243-2